The Grail Diary

How I got onto this sketchjournaling kick

I still remember being 8 years old and seeing Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade for the first time. My parents had bought it on VHS some years earlier and I was finally deemed old enough to handle the more dramatic and mature elements of the film. I remember being completely swept up into the high adventure of the plot. Even at that precocious age, my young heart thirsted for that kind of adventure — the mystery, the thrill of the chase, the scavenger hunt that sprawled across ancient and hidden places, so far removed from my rural Idaho home. I wanted to find clues in forgotten old books to things others missed, I wanted to pack up and set sail across oceans to see them with my own eyes, and I wanted to touch antiquities and relics spanning generations and appreciate them for what they are1. A fire was set alight in my little soul that persists to this day, that it isn’t quite enough to merely read about adventure, I want to experience a bit of it for myself. (There are plans in the works, to be sure. But I digress.)

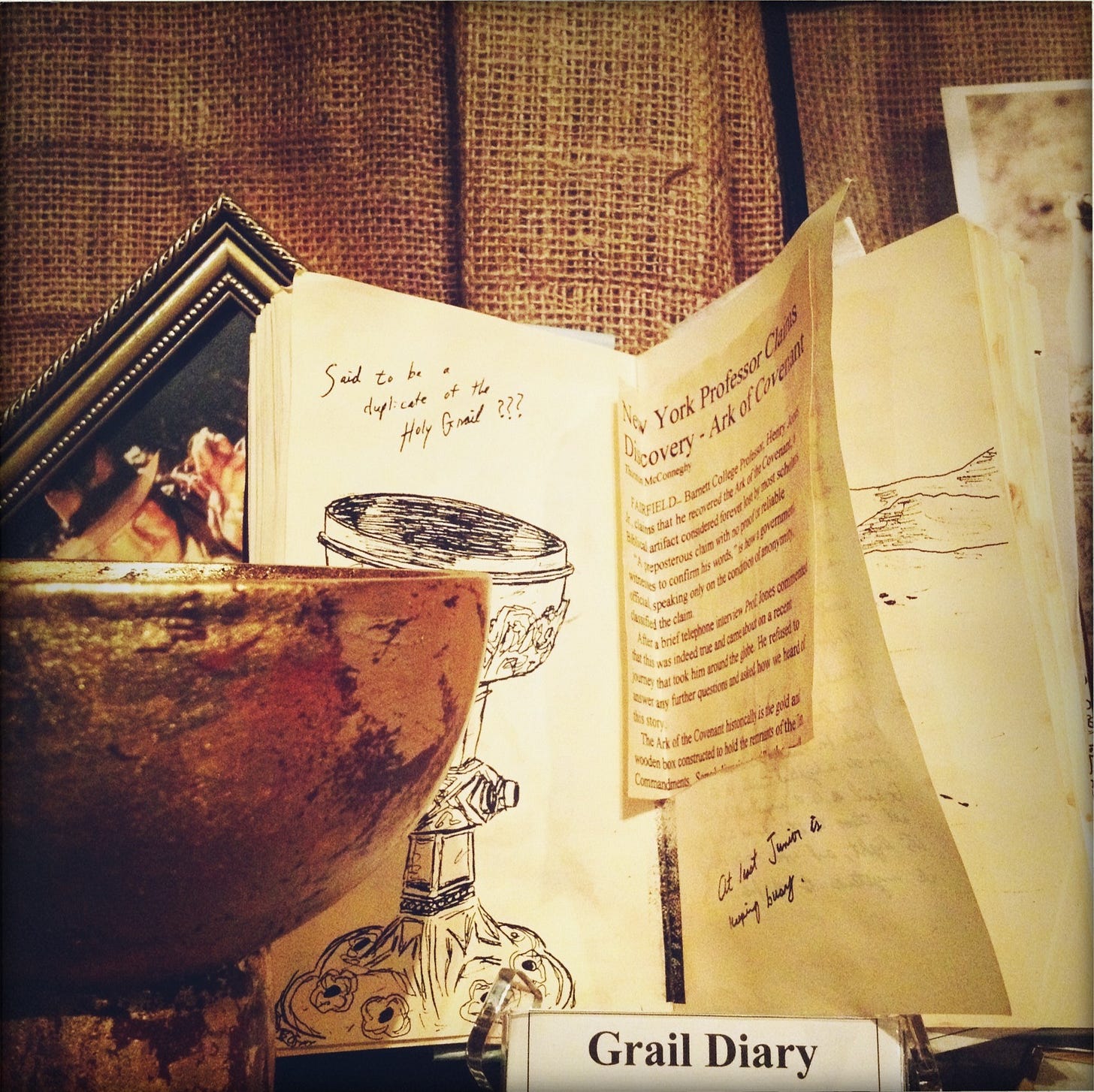

One of the ideas that gripped me the most, however, was how Dr. Jones Sr. had compiled all the information in a little book: what is known in fan circles as “the Grail Diary.”

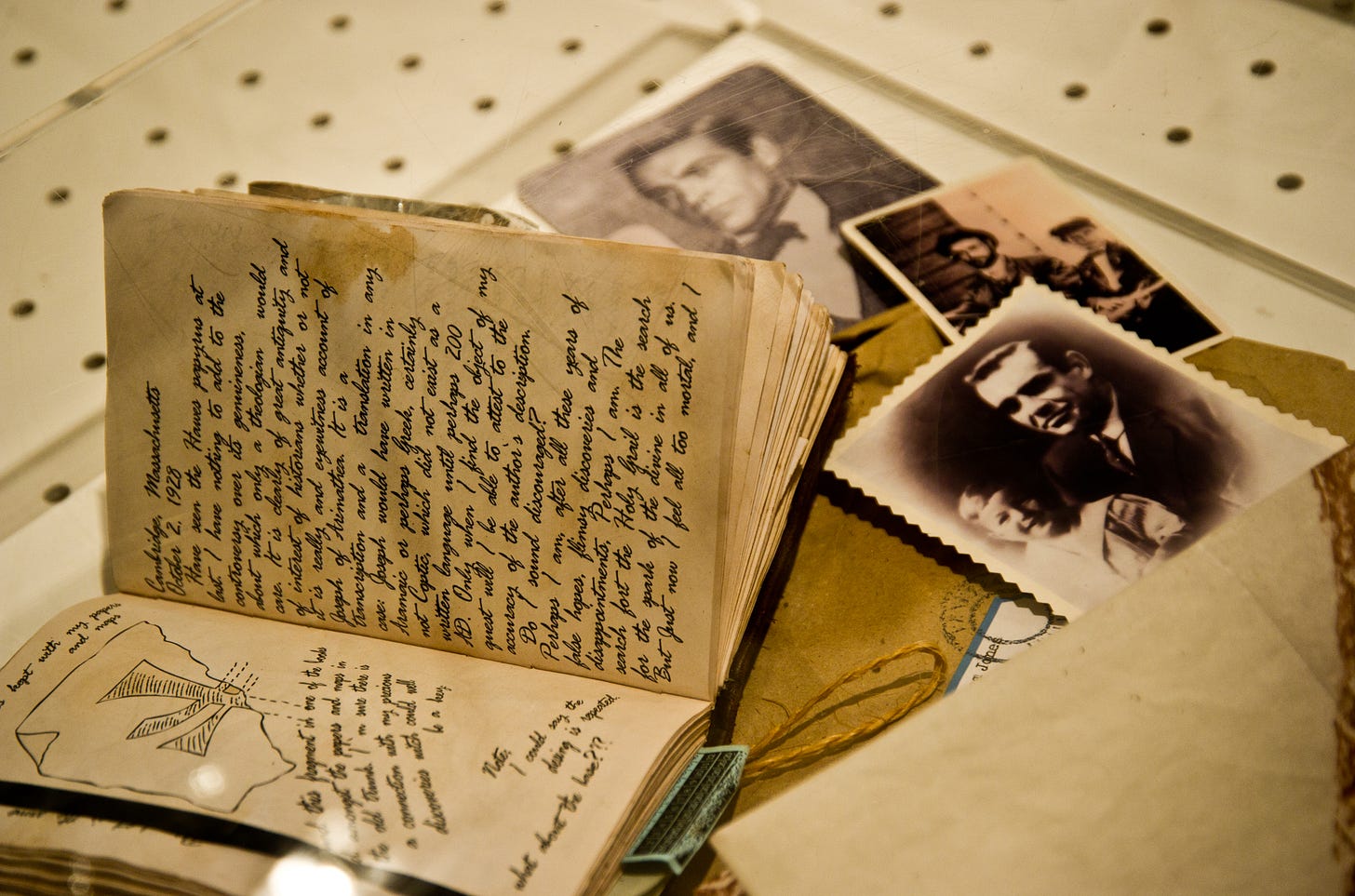

As a child, my love of books had fed into a love of writing, but this was the first time I saw handwriting combined with art. And it inspired me immensely; I had absorbed the belief somehow that writing and art should not be combined on a paper (I probably got in trouble for doodling in the margins in school), and yet here was this amazing book with both, side by side. There is a scene where Jones and his fellow adventurers are in the library in Venice, and we get a good look at the diary as he compares it to a stained glass window:

If you look quickly, you can see the varied design of several pages, some with more text, some with less, and artwork side by side with ticket stubs and other bits of scratch paper tucked in around them. Something about the hodgepodge powerfully mirrored the way I processed my own world, and I was smitten. This was the system for me. When my childhood enthusiasm failed to recreate my own Grail Diary, I settled for keeping my artworks and writings in a small binder (the closest I could come to a hardcover journal at the time). My artist grandmother couldn’t understand why I wanted to keep everything in one booklet — in her mind, art should be displayed on the wall — but I had found a system that worked. Throughout the rest of my childhood, I would bounce back and forth from writing to art, until adulthood stole my time and attention.

Nearly 15 years later, when I was returning to art-making, I immediately gravitated to a set of 3x5-inch hardcover pocket sketchbooks I had found at Walmart. And I couldn’t settle on whether I should draw in it or write in it, so I did both, remembering with fondness my childhood preoccupation with the Grail Diary. Documenting the journey, one sketch and sentence and bit of ephemera at a time.

Time and time again, no matter how many artistic forays elsewhere I take, I always return to what I now refer to as the sketch-journal.

Today, the Grail Diary is in a museum dedicated to preserving memorabilia from the American motion picture industry, where it continues to inspire many to make accurate prop reproductions for cosplay, and perhaps, a few who will take the idea and run with it in new ways.

Around this time I similarly became preoccupied with the story of Howard Carter and the supernatural curse of Tutankhamun’s tomb, Bob Ballard who discovered the wreck of the Titanic, as well as other stories that blended history, science, the supernatural, and adventure — a formative predilection that has no doubt fueled my love for art history and my steady pursuit of higher levels of education. And come to find out, journaling in both text and visual formats is a common feature of many famous explorers, scientists, professors, and adventurers’ careers.